Wondering why the United States measures things in inches and pounds? The answer will definitely surprise you

Why Doesn’t the United States Use the Metric System?

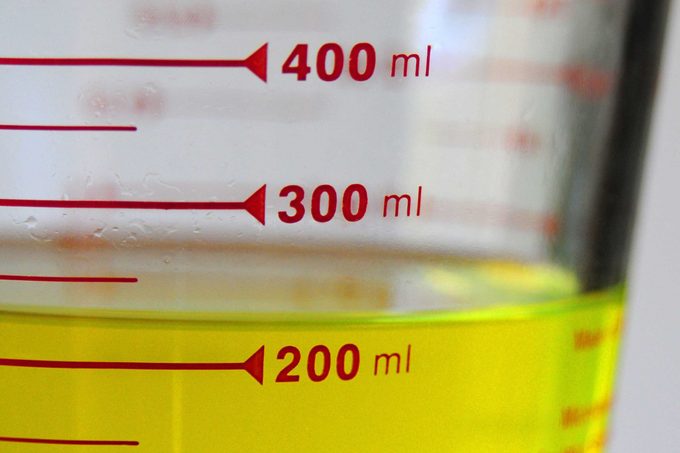

Have you ever noticed that systems of measurement tends to change when you leave the United States? Weight is typically measured in kilograms instead of pounds, distance is measured in kilometers over miles, and volume is measured in liters rather than ounces. But that’s not all: we also measure temperature in degrees Fahrenheit instead of Celsius. While most of the rest of the world uses the metric system (formally known as the International System of Units, or SI), the United States uses the U.S. Customary System, which—fun fact—is often mistakenly referred to as the “imperial system.” So, why doesn’t the U.S. use the metric system? Reader’s Digest spoke to experts in the metric system to find out. Here’s what we learned about the history of the metric system, and the reasons why the United States hasn’t fully adopted the system favored throughout most of the rest of the world.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more interesting facts, humor, cleaning, travel and tech all week long.

What countries use the metric system?

All countries use the metric system to varying degrees. Most of the world has adopted the metric system as their official system of measurement with one major exception: the United States. “The U.S. stands out as the only major industrial nation that doesn’t use the metric system,” says Donald W. Hillger, PhD, president of the US Metric Association. Having said that, the United States hasn’t avoided the metric system completely.

Although the United States hasn’t adopted the metric system as the sole system of measurement, in reality, we use the metric system every day. “This is particularly the case in medicine—think grams of medication, for example—certain types of liquid measurement, like liters of soda, and some sports and athletic events,” says Stephen Mihm, PhD, a history professor and associate dean of the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Georgia. “We don’t think anything of the fact that we use both systems—we’re bilingual, at least in certain contexts.”

According to Hillger, the general consensus among experts is that the U.S. is essentially half metric. “About 50% of the measurements you encounter in anything have to do with the metric system,” he notes. This includes everything from food labels and pharmaceuticals to electronics, machinery, cars and wrenches. “But most people don’t encounter [the metric system] because they don’t turn the wrenches,” he explains. “They don’t look behind the scenes. They don’t look under the hood and see all that metric that’s there.”

So, what about the rest of the world? Hillger says that even countries that have fully adopted the metric system also measure certain things in U.S. customary units or their own local system of measurement. “Even in your best metric countries, they’re probably 95% metric,” he explains. “There’s a number of things around the world—like pipe sizes for the oil and gas industry—that are not based on the metric system. But everybody uses those, even in metric countries, because the United States started the drilling eons ago.”

What countries don’t use the metric system?

It is commonly reported that along with the United States, Myanmar and Liberia also haven’t adopted the metric system, but that’s incorrect. In 2013, Myanmar’s Ministry of Commerce announced that the country would adopt the metric system. Five years later, the Liberian government pledged to do the same. Both are reportedly in the process of converting to the metric system.

The U.S. Metric Association relies on a map created by Peter Goodyear—a retired electronic technician and IT worker, and one of the moderators on Reddit’s metric forum—to keep up with the use of the metric system around the world. The U.S. is in a category of its own, as the use of the metric system is voluntary. The U.K. and its territories is also singled out, as road signs still use miles and miles per hour, and draught beer and cider and bottled milk are sold in pints. Canada, Belize and the Philippines are also grouped together for having adopted the metric system, but continuing to use non-metric units regularly. Finally, Somalia, Malaysia, Myanmar and Liberia have all adopted the metric system, but still frequently use non-metric units.

So, why, out of all the countries in the world, is the United States the only one that hasn’t officially adopted the metric system? As it turns out, there are multiple reasons why we’ve stuck with customary units.

The history of the metric system in the United States

When British settlers colonized what would become the United States, they brought their system of measurement with them: a hodgepodge of Anglo-Saxon, Roman and Norman folk traditions. The United States and United Kingdom shared a system of measurements until 1824, when the Weights and Measures Act standardized the existing British customary units, changing them slightly, and establishing the imperial system in the UK. Meanwhile, the United States stuck with their existing system. This is why it’s incorrect to refer to the system of measurement used in the U.S. as the “imperial system.” According to Hillger, there’s no official name for our current system of measurement. “That’s why we tend to lean towards ‘customary units,’ because that’s what’s generally customary in the United States,” he says.

Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power “to fix the standard of weights and measures,” so it would take an act of Congress for the United States to officially adopt the metric system. While Congress legalized the use of the metric system via the Metric Act of 1866, as Mihm points out, “that is not the same as making it mandatory or the only system of measurements.” The next major directive didn’t come from Congress: it came from T. C. Mendenhall, then Superintendent of Weights and Measures, in 1893. Known as the “Mendenhall Order,” it re-defined U.S. customary units in terms of metric units. “For example, the inch is defined now as 25.4 mm exactly,” Hillger says. “Similarly, the pound is defined based on the kilogram.”

Why doesn’t the U.S. use the metric system?

Today, scientists, engineers and manufacturers tend to be proponents of the metric system, but that wasn’t always the case. In the late-19th and 20th centuries, the most damaging attacks on the metric system came from progressive engineers, entrepreneurs and industrialists who had created the country’s industrial standards during a time of rapid industrial growth.

“Far from being backward-looking reactionaries, they enjoyed reputations as cutting-edge leaders in the development of the machine-tool industry, the railroads, and the metal-working industries,” Mihm writes in a journal article titled “Inching toward Modernity: Industrial Standards and the Fate of the Metric System in the United States. “Many of them pioneered new methods of management that privileged rationality, efficiency, and systemic approaches; indeed, they strongly influenced the development of what became known as scientific management.”

After establishing and implementing these approaches, it’s not surprising that engineers and industrialists were against conversion to the metric system. “Efforts to mandate the metric system in the early 20th century failed because industrialists objected—with some good reason—to retooling the entire system of measurement in manufacturing,” Mihm explains. “This would have been costly, and these concerns ultimately prevailed.”

One area where the metric system has made headway in the U.S. is in schools. The metric system typically wasn’t taught in American elementary schools prior to 1972, but that changed in 1974 with the Metric Education Amendments. “Teaching the metric system in American schools is important since all industrialized nations utilize this system except for the United States,” says Christine Anne Royce, EdD, professor of education and co-director of the Master of Arts in Teaching in STEM Education Program at Shippensburg University and a past president of the National Science Teaching Association. “For students who wish to enter any of the STEM fields, it is essential that they understand the system that will allow them to work, communicate, and ultimately engage in the different fields themselves.”

The following year saw another attempt at promoting the metric system in the United States. But the Metric Conversion Act of 1975 was voluntary, “so the government really didn’t force anybody to go metric,” Hillger says, though it did permit companies to make the switch. The law established the U.S. Metric Board, which was tasked with helping with the transition, but according to Hillger, wasn’t very effective. “They had a lot of people on the board that didn’t really want the metric system, and all they ended up doing was fighting about it and not really doing very much at all,” he explains. “One of the things they tried to work on most was to get gas pumps to change from gallons to liters, and did a very poor job of that.”

So why didn’t the U.S. adopt the metric system in 1975? Hillger says that the law failed because it didn’t make the metric system the standard system of measurement in the US. “If you don’t have some kind of a standard, you’re just going to have a terrible mix of units,” he says. “I’m not a fan of the government forcing people to do things, but on the other hand, they really could have encouraged it more.” And ultimately, the campaign accompanying the law didn’t sway public opinion on the metric system. “People didn’t see the need for it, and there was also a lot of resistance to doing anything different,” Hillger says.

Generally speaking, Mihm says that our system of government has made conversion to the metric system harder than it is in other countries. “The United States operates within a federal system, dividing power between the national government and the states,” he explains. “This has likely made it more difficult to mandate the metric system than in nations where there is a much stronger central government.” Along the same lines, Mihm says that another reason has to do with the dominance of the United States in the global economy. “Other nations have often been forced to adopt the metric system by virtue of trading with other metric nations,” he says. “As the world’s largest economy for most of the past 150 years, the United States has had the luxury of maintaining a dual system, imposing its own measures on other countries when it wishes to do so.”

Will the U.S. ever adopt the metric system?

Will the U.S. ever fully make the switch to the metric system? Royce believes that the metric system will continue to be taught in schools and used in certain fields, like science and engineering, but says that adopting it as the sole system of measurement is unlikely. “With as many different places where measurements are listed, it would be a massive undertaking to switch to only metric,” she explains. Mihm, meanwhile, thinks the U.S. will join the rest of the world in using the metric system, “probably take another century—at least.” Hillger also believes that it’s only a matter of time before the U.S. adopts the metric system. “We’re eventually going to get there,” he says. “I say it’s inevitable, but I won’t put a date on it.”

In order for the U.S. to have a chance at adopting the metric system, Hillger believes that it’s a matter of Congress taking action. “If we really want to be a metric century country, Congress has to act,” he says. “We really have to have some legislation passed—otherwise, I don’t think we’ll ever get as complete [a transition to the metric system] as we would like to see.” But in the meantime, he believes that the use of the metric system in the US will continue to grow over time—especially as new technologies tend to be developed using the metric system in order to meet international standards.

Additional reporting by Carly Lerner

About the experts

|

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. For this piece, Carley Lerner tapped her experience as a journalist who covers interesting facts and trivia for Reader’s Digest. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Stephen Mihm, PhD is a history professor and associate dean of the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Georgia. He specializes in business history and is currently writing a history of standards and standardization in the United States for Harvard University Press.

- Christine Anne Royce, EdD is a professor of education and co-director of the Master of Arts in Teaching in STEM Education Program at Shippensburg University. She is also a past president of the National Science Teaching Association.

- American National Standards Institute. “US Customary System: An Origin Story”

- CBC. “As the U.K. brings back imperial measurements, is it time for Canada to drop them?”

- U.S. Metric Association. “Adoption of the Decimal System of Weights and Measures by Country”

- International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. “The US failure to adopt the metric system: the high cost of teaching the English system”

- Liberian Observer. “Gov’t Pledges Commitment to Adopt Metric System”

- Eleven. “Myanmar to Adopt Metric System”

- Peter Goodyear. “World Metric Map”

- Journal of Government Information. “Take Me to Your Liter: A History of Metrication in the United States”

- United Kingdom. “Weights and Measures Act 1824”

- UK Metric Association. “UK Metric Timeline”

- The United States of America. “Constitution of the United States: Article I”

- U.S. Congress. “Metric Conversion Act”

- Library of Congress. “An Act to authorize the Use of the Metric System of Weights and Measures”

- Stephen Mihm. “Inching toward Modernity: Industrial Standards and the Fate of the Metric System in the United States”

- United States Metric Association. “Mendenhall Order”