The true story of Tarzan is stranger than fiction. With the help of a historian and Tarzan expert, we set the record straight.

Our editors and experts handpick every product we feature. We may earn a commission from your purchases.Learn more.

The true story of Tarzan is stranger than fiction. With the help of a historian and Tarzan expert, we set the record straight.

Our editors and experts handpick every product we feature. We may earn a commission from your purchases.Learn more.

Whether you’ve seen the animated Disney movie, read the classic book or just swung from a rope as a kid while doing the famous yell, chances are you’ve heard of Tarzan—even if you don’t know where the story originated. According to legend, he was a child stranded in the jungle and raised by apes, only coming into contact with humans later. But is Tarzan based on a true story? We used our super-sleuthing skills to get to the bottom of this literary mystery.

Turns out, the truth about Tarzan is stranger than fiction, as we discovered when we contacted film and pop-culture historian Scott Tracy Griffin, author of Tarzan: The Centennial Celebration and Tarzan on Film. The mystique of this fascinating character has captured imaginations since the tale was first published by Edgar Rice Burroughs in the pulp magazine The All-Story in 1912 and has endured as the story became one of the best books of all time. The secret of Tarzan‘s creation is no less intriguing.

“Tarzan is aspirational, a timeless character embodying the human potential, one that cuts across cultural lines,” Griffin says. “Anyone can fantasize that they are king of the jungle and absolute ruler of their own domain.” If there was a real-life Tarzan, his would be a truly extraordinary adventure.

So is Tarzan based on a true story? We dove into the historical records and talked to our expert on the topic to set the record straight.

Join the free Reader’s Digest Book Club for great reads, monthly discussions, author Q&As and a community of book lovers.

In case you need a quick recap of the story, here’s the basic plot of Burroughs’s first Tarzan novel, Tarzan of the Apes: After his family is marooned in Africa and his parents die, a white child is raised by primates in the jungle. He learns the apes’ ways and grows up to usurp the alpha male as king of the jungle. He swings from vines, has a trademark call of the wild, is introduced to a bunch of abhorrent humans and his love interest, Jane, and eventually discovers he’s really an English lord.

The book series was an immediate, massive hit, and Burroughs capitalized on that popularity by writing two dozen sequels.

Where Burroughs got the idea for his hit series and whether it came from a true story is complicated. That’s partially because the author played coy on the subject. “Burroughs was a humble and modest man, asserting that he only wrote to escape poverty, but his creative genius is undeniable,” Griffin says. “He was always cagey about his inspiration for Tarzan, insisting that his primary source was the tale of Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome who were adopted by a she-wolf.”

Burroughs was well-versed in the classics of Greece and Rome, which he studied during his school years, Griffin says. “His familiarity with the formula of the heroic epic helped shape his tales into classics that span generations,” he says.

Burroughs may have been so secretive about the origins of his idea because he was plagued by accusations of copying Rudyard Kipling, whose Jungle Book was published years earlier in 1894 and featured Mowgli, a boy raised by wolves, befriended by other animals and eventually faced with both internal and external human dilemmas. (Coincidentally, it was also turned into a Disney cartoon and a live-action film.)

Kipling himself thought Burroughs was a copycat: In his 1937 autobiography, Something of Myself, Kipling wrote, “He had ‘jazzed’ the motif of the Jungle Books and, I imagine, thoroughly enjoyed himself.”

But Kipling wasn’t the first writer to come up with the idea of a man isolated in the wild with only animals as companions. “There were a few fictional stories in this vein, such as the 1888 novel Captured by Apes by Harry Prentice and the 1879–80 French pulp stories by Albert Robida, Voyages Très Extraordinaires de Saturnin Farandoul, which were translated in an 1880 edition of the U.S. humor magazine Puck as ‘The Monkey King,’” Griffin says.

As with many literary tropes, it’s difficult to identify who really came up with the original idea. So was Tarzan a mere imitation of stories that had come before? “Burroughs never identified any real-life inspirations for the character and downplayed any influence of Rudyard Kipling’s character Mowgli from The Jungle Book,” Griffin says.

Although theories abound about other stories that may have inspired Burroughs, “there is no paper trail between most of these works and ERB,” Griffin says, using the nickname popular among Burroughs scholars. “If ERB read them, he never commented on that fact, so sources beyond Romulus and Remus, and Kipling, are purely speculative.”

End of story … right?

Like a good book, the plot thickens. Rumors have swirled for decades that Tarzan was actually based on a real-life person—and they were possibly fueled by Burroughs himself. “In correspondence with professor Rudolph Altrocchi of the University of California at Berkeley, Burroughs cited a vague recollection of the story of a shipwrecked sailor adopted by apes,” Griffin says. “But Altrocchi was unable to find such a source, as reported in his 1944 book, Sleuthing in the Stacks.”

The Tarzan novel itself also teases the idea of a man behind the myth. “The first story, Tarzan of the Apes, asserts that the tale may be true and that the names have been changed to hide the identity of the principles,” Griffin says. “This is generally regarded as a literary device.”

After all, the story posits that Tarzan’s upbringing among the apes resulted in superhuman strength, heightened sensory perception and animal cunning, coupled with human intelligence and innate nobility—which is too outlandish for the novel to be anything other than a fantasy book. Rather, it’s “a compelling, if fictitious, portrait of a man,” Griffin says.

This is where the story of the real-life Tarzan gets really bizarre. Google “Is Tarzan based on a true story?” and you will get a plethora of articles about the supposed real-life Tarzan, William Mildin, the 14th Earl of Streatham—even from some usually trustworthy publications.

Who was this earl? Allegedly, family documents unearthed after Mildin’s son died in 1937 told a thrilling tale of shipwreck and adventure. According to the elder Mildin’s 1,500 handwritten pages of memoirs, the earl spent years in the wilds of Africa (like Tarzan) after a job on a boat went terribly wrong.

His papers begin, “I was only 11 when, in a boyish fit of anger and pique, I ran away from home and obtained a berth as cabin boy aboard the four-masted sailing vessel, Antilla, bound for African ports of call and the Cape of Good Hope …” His ship was destroyed during a three-day storm, and he claimed he survived by clinging to a “piece of the wreckage.” He wrote that he washed ashore somewhere between Pointe Noire and Libreville in French Equatorial Africa. Allegedly, official insurance documents proved the Antilla had been totaled in 1868.

Mildin’s memoirs claim he took up with a group of apes after they provided him with food, saying, “For some strange reason, I was not afraid of these strange creatures. They were hideous to look upon but seemed gentle and harmless.” He writes that they gave him nuts, grubs and roots. He was starving, so he ate the cast-offs, which apparently were rejected by his system at first. “I was terribly ill afterwards, and the apes appeared to understand this. One ancient female hunched her way over to me and cradled me in her arms.”

He returned the favor to the family by making fire and stealing weapons from an Indigenous settlement: “I found new and easy ways to root under logs for grubs and dig for roots with a sharp-tipped stick.” He talks about dressing their wounds with cool moss or wet mud. He “gathered branches to make a crude tree house.”

Mildin brags that he was “unusually strong and agile for his age” but never claims he became the leader of the animals. “The brutes came to look upon me, not as a leader, for I could not match their feats of strength and endurance, but as a mute well-intentioned and helpful counselor.” Eventually, though, he returned to his homeland to claim his title and estate, with an 1884 report from Fort Lamy in present-day Chad allegedly confirming Mildin came through there to get home.

Here’s the kicker: No such person ever existed. The story of the “real” Tarzan is, ironically, itself a fictional creation—and has been proven to be so. “A March 1959 issue of Man’s Adventure Magazine asserted the Tarzan story was based on the real-life tale of William Charles Mildin, the 14th Earl of Streatham, but that claim was a hoax,” Griffin says.

The article, “The Man Who Really Was … Tarzan,” was a sensational tall tale. These types of adventure magazines usually printed embellished or fictional stories, Griffin says. All of Mildin’s journal entries, and all the supporting “evidence” of his story, were made up—another literary device for a fictional piece.

When the unearthed Man’s Adventure article began making the rounds on the internet decades later, it was so convincingly written that it was taken as truth—without any confirmation of the existence of Mildin, his memoirs, the insurance claims or the shipwreck. “The Mildin story is just another example of something going viral on the internet without proper vetting and fact-checking,” Griffin says. (Mea culpa: An older Reader’s Digest article did just that.)

Even though the Man’s Adventure story “cites” newspaper articles from an actual publication, The London Times, later searches did not find anything in their archives, Griffin says—but not before other journalists had repeated the false information. “Subsequent reporters never bothered to seek additional primary sources or check The Times for the alleged articles on Mildin,” he says.

It seems the Man’s Adventure story was just a really good, completely compelling piece of pulp fiction that turned into an urban legend.

We had to go even further, though, to prove that Mildin was not real in order to solve this mystery for good. After a deep dive on the internet turned up no other record of Mildin or the title of Earl of Streatham (except as it related to the Tarzan story), we went to Burke’s Peerage, one of the foremost authoritative guides to the records of historical families and titles of the United Kingdom, for confirmation of whether Mildin or the title was real.

Was there a person named William Mildin, the 14th Earl of Streatham? If not, was there ever even a hereditary title of the Earl of Streatham, either among the current 191 English earls or in the past?

Their response to our query was simple: “Neither the person nor title ever existed.” Case closed.

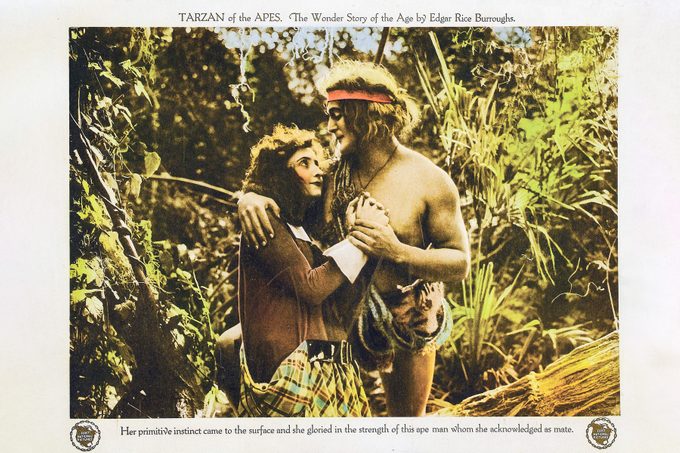

Given that Tarzan wasn’t based on a real person, it’s probably no surprise that Jane wasn’t either. First appearing in Tarzan of the Apes—A Romance of the Jungle, published in 1912 in The All-Story, she was purely a figment of Burroughs’s imagination. “Burroughs never indicated that Jane, a blonde Southern belle from Baltimore in the novels, was based on a real person,” Griffin says. Jane’s introduction was such a hit that it spurred Burroughs to write a bunch of tales about the pair’s life together in the jungle.

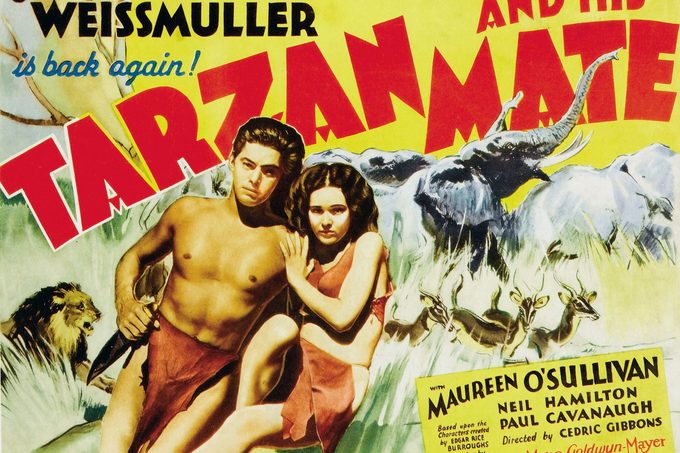

The popular movie adaptations from the 1930s and ’40s capitalized on the sex appeal of the character. Onscreen Jane also deviated from the character’s original genteel persona from the books, Griffin says. “Janes in the ape-man theatrical and telefilms speak with inflections ranging from British (Minnie Driver) to mid-Atlantic (Maureen O’Sullivan) to New York (Kim Crosby),” he says. “In the early movies, the character was presented as the love interest, but contemporary iterations see her as a modern woman in careers that include cabbie and cop.”

But Tarzan famously inspired one real-life Jane, primatologist Jane Goodall, to live among the apes in Africa after she read the books as a child. “I had read Tarzan and fallen in love, although he married the wrong Jane,” she has said, repeating a joke she’s used many times. “I wanted to live with wild animals and write books about them.” There’s even a wonderful children’s book, Me … Jane, that references Tarzan and his famous dialogue while telling Goodall’s story for young readers.

The theme of Tarzan and stories like his—a white man going to a strange, “exotic” or “wild” continent and becoming a leader there—has understandably been viewed through modern eyes as a colonialist, imperialist and even racist trope. Tarzan is also problematic for today’s audiences by centering a white outsider’s experiences and perceptions of Africa, rather than those of an indigenous Black person.

The perspectives in the original Tarzan stories were a product of their time, just like Jungle Book author Kipling’s infamous poem “White Man’s Burden,” in which he justified colonialism. “Reading the books as a child, I realized that some of the attitudes were from another era, just as I did with other classical literature, like Huckleberry Finn, Robinson Crusoe and the tales of H. Rider Haggard,” Griffin says. “This didn’t inhibit me from enjoying the page-turning adventure of the tale.”

He also thinks there’s another way to interpret the Tarzan story. “The character spends much of his time fighting outside invaders from civilization who would despoil the jungle and its riches,” he says. “In that regard, Tarzan seems more of a conservationist.”

There have been over 50 Tarzan movies, from 1918’s silent Tarzan of the Apes to the Johnny Weissmuller–led flicks of the ’30s and ’40s to multiple movies from the ’50s through ’70s. There was also a 1966–68 NBC television series with Ron Ely (who just passed away this September) and a 1970s animated children’s program. In the 1980s and ’90s, several more movie adaptations came to the screen, including 1984’s Oscar-nominated GreyStoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes.

The most well-know book-to-movie adaptations for today’s audiences are undoubtedly Disney’s 1999 animated movie Tarzan and The Legend of Tarzan, a 2016 live-action flop starring Alexander Skarsgård and Margot Robbie. You’ve probably also heard comedian Carol Burnett famously doing her “Tarzan yell” in sketches since the 1960s—the 91-year-old even let it loose in her latest Emmy-nominated role—a spot on the 2024 Apple TV+ series Palm Royale.

Tarzan‘s impact, though, goes way beyond the screen. “The books have been translated into at least three dozen languages and spawned a licensing empire that included 52 authorized films, radio and television programs, two Broadway shows, comic books and newspaper strips, and a host of merchandising—toys, games, apparel, paper goods, food products, collectibles and many more,” Griffin says. “Tarzan has also endorsed items like bread, ice cream and gasoline ‘with the power of Tarzan.’”

Now a permanent fixture in pop culture, Tarzan is instantly recognizable to every American—and beyond. “Tarzan has had an immense global impact and is one of the most recognized brand names worldwide, along with characters like Superman and Mickey Mouse,” Griffin says. But perhaps Tarzan’s most important legacy has been on the generations of conservationists, like Goodall, who he’s inspired to work to preserve the environment and wildlife of Africa.

Additional reporting by Carrie Bell.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more books, entertainment, humor, travel, tech and fun facts all week long.

About the expert

|

At Reader’s Digest, we’ve been sharing our favorite books for over 100 years. We’ve worked with bestselling authors including Susan Orlean, Janet Evanovich and Alex Haley, whose Pulitzer Prize–winning Roots grew out of a project funded by and originally published in the magazine. Through Fiction Favorites (formerly Select Editions and Condensed Books), Reader’s Digest has been publishing anthologies of abridged novels for decades. We’ve worked with some of the biggest names in fiction, including James Patterson, Ruth Ware, Kristin Hannah and more. The Reader’s Digest Book Club, helmed by Books Editor Tracey Neithercott, introduces readers to even more of today’s best fiction by upcoming, bestselling and award-winning authors. For this piece, Tina Donvito, a longtime journalist with a degree in English and history, interviewed Tarzan expert Scott Tracy Griffin to ensure that all information is accurate and offers the best possible advice to readers. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources: