There’s so much more to Baby New Year than a cute cartoon figure. See if you can guess when he was “born” and what he represents.

This Is the Fascinating Origin of Baby New Year—and It Goes Back Much Further Than You Probably Think

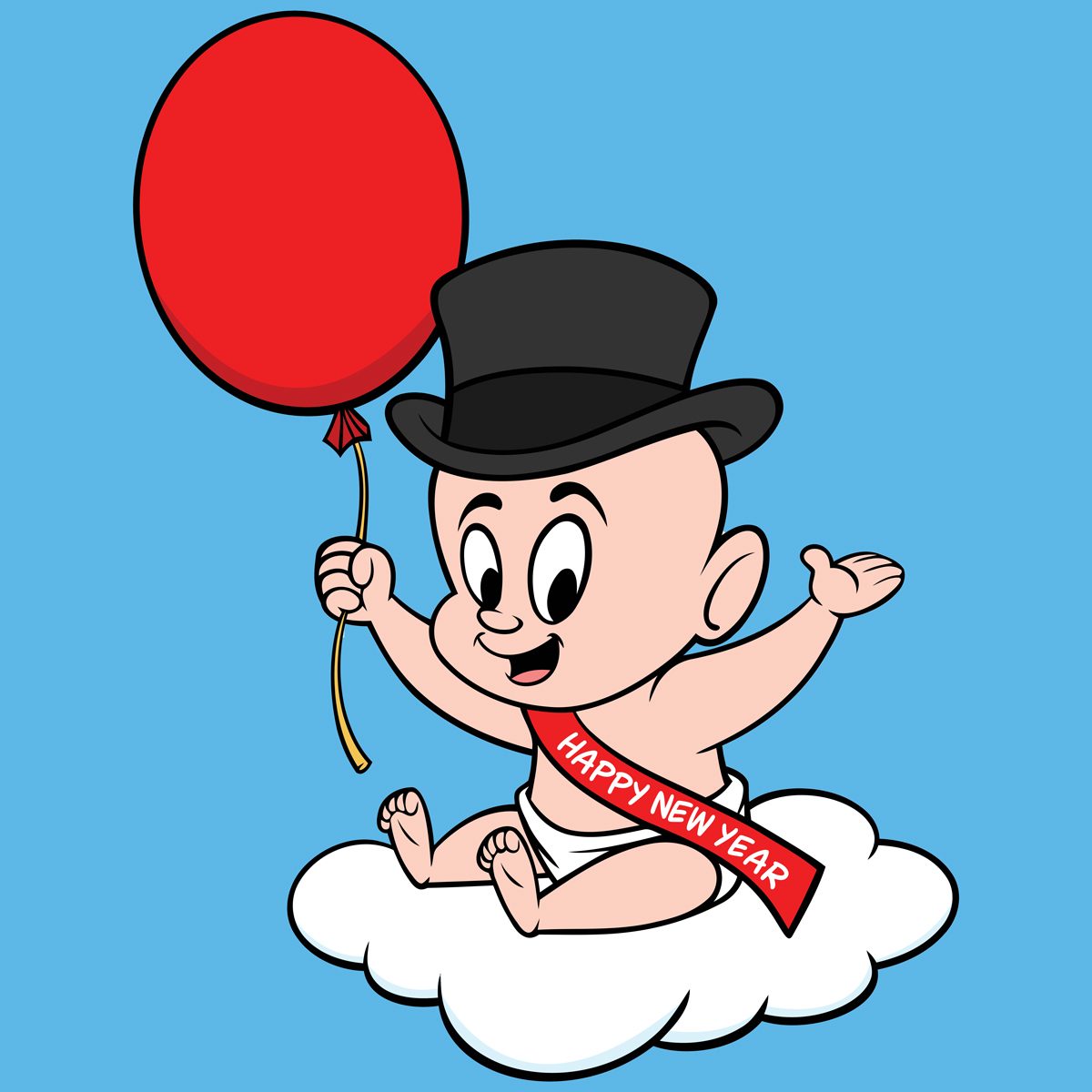

Christmas has Santa. Easter has the bunny. And the new year has … a baby? That’s right: Each year at the stroke of midnight on Jan. 1, a bouncing baby boy—aptly named Baby New Year—symbolically crawls into our lives to mark the beginning of another one of Earth’s trips around the sun.

Sure, he’s cute and all, but why is the new year represented by a baby? And where does this baby come from? We spoke with Daniel Compora, PhD, a professor in the department of English language and literature at the University of Toledo, and mined ancient history and folklore to find out. Here’s what to know about the origins of Baby New Year and how the infant became a New Year’s tradition.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more holidays, humor, cleaning, travel, tech and fun facts all week long.

Who is Baby New Year, exactly?

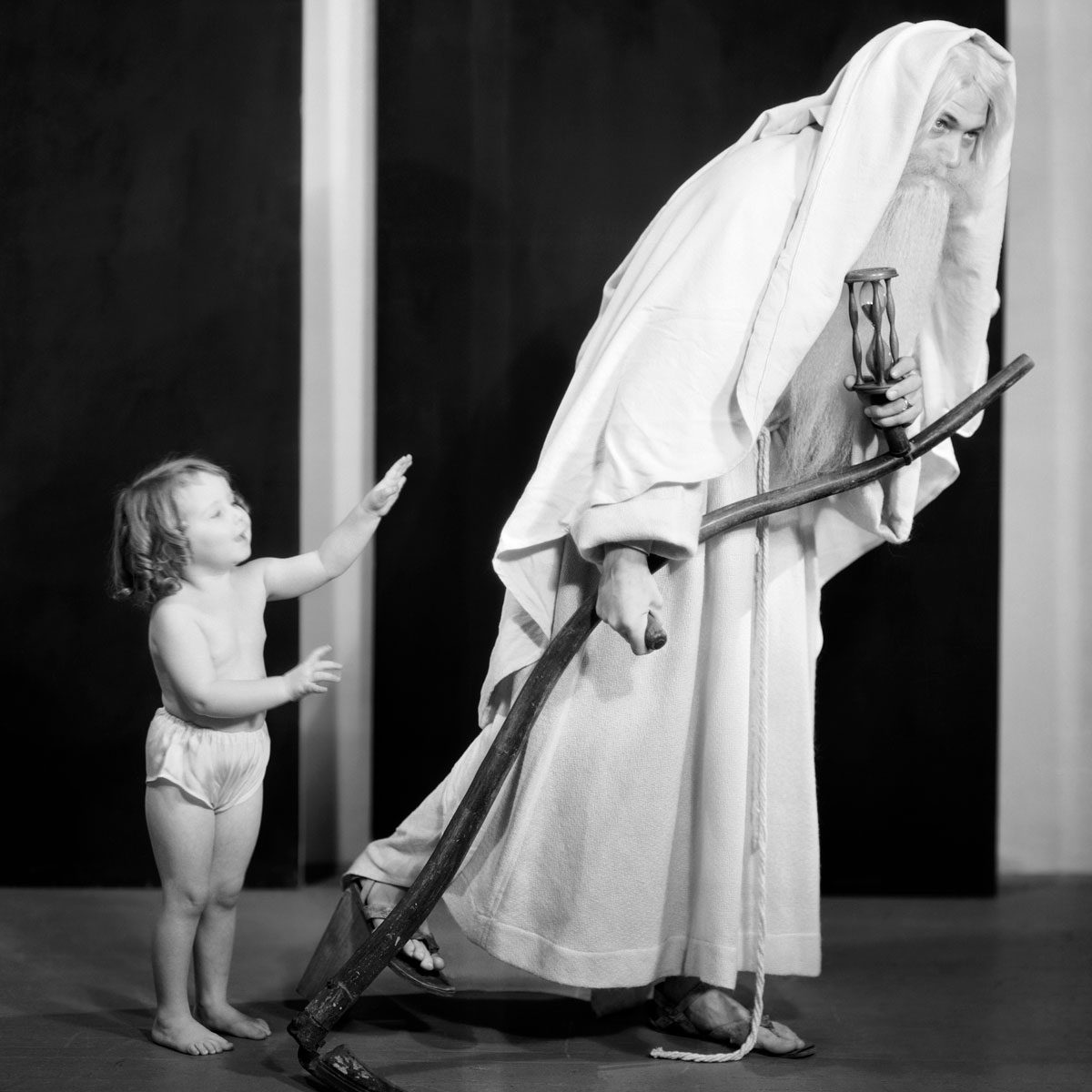

Baby New Year is a symbolic representation, or personification, of the passing of the previous year and the ushering in of a new one, says Compora. This concept is meant to show the passage of time over the course of one calendar year, as represented by human life: a person born on Jan. 1 who ages and becomes an older man on death’s doorstep by Dec. 31. “Since the new year is a way to start over again, it represents rebirth or starting over,” Compora explains.

What is the origin of Baby New Year?

Baby New Year is traditionally depicted as a baby or toddler wearing a diaper, loincloth or toga—and often a sash bearing the new year—but otherwise nude. Sometimes the baby is wearing a party hat, like those who ring in the new year at midnight. Other times, he’s depicted with wings, like Cupid.

The origins of Baby New Year can be traced back to Ancient Greece—specifically, an annual celebration known as the Great Dionysia, according to William Crump in his book Encyclopedia of New Year’s Holidays Worldwide. Originally, the festival wasn’t tied to the new year; instead, it commemorated the winter death and springtime resurrection of Dionysus, god of wine, vegetation and fertility. During the festivities, the birth of Dionysus was reenacted by placing an infant in a winnowing fan, a type of bread basket.

What is Baby New Year’s relation to Father Time?

Father Time—typically depicted as an elderly man with a long white beard—is the end-of-year counterpart to Baby New Year. In other words, in this scenario, the passage of one year corresponds to one human lifetime. As noted above, the person is born as Baby New Year on Jan. 1 and gradually ages as the months pass until he reaches the end of his life as Father Time on Dec. 31. Baby New Year and Father Time are often shown together.

According to Compora, the elderly image of Father Time is most likely drawn from Chronos, the Greek god of time, or the Roman god Saturn. Like Father Time, each was often depicted carrying a scythe, like the Grim Reaper. But Compora says that Father Time may have also been inspired by the two-faced Roman God Janus, who represented beginnings and endings, as well as life and death. “The Father Time persona appears to be an amalgamation of these various figures,” he says.

How did this tradition evolve over the millennia?

The tradition of celebrating rebirth and renewal with a symbolic baby spread from Ancient Greece to other parts of Europe. According to Theodor Gaster in the book New Year: Its History, Customs, and Superstitions, the image and tradition of Baby New Year was brought to the United States by German immigrants—specifically, through an obscure 14th-century folk carol in which a baby serves as a symbol for the new year.

The image and concept of Baby New Year became more widespread in both Europe and the United States during the Victorian era, thanks to the massive popularity of greeting cards and postcards. Advancements in printing technology meant that colorful illustrations could be mass-produced. In addition to Christmas cards, people sent cards to wish others luck in the new year—many of which were adorned with pictures of Baby New Year, sometimes alongside Father Time.

A different type of illustration kept Baby New Year in the public eye for the next several decades. From 1907 to 1943, illustrator (and mentor to Norman Rockwell) J.C. Leyendecker drew depictions of Baby New Year for the covers of the Saturday Evening Post. Starting in the 1910s, Leyendecker began referencing contemporary events in his iconic illustrations, like a baby flying an airplane in 1910—a nod to the era’s fascination with aviation—and a baby carrying a “Votes for Women” placard in 1912, during the ongoing campaign for women’s suffrage.

A few decades later, Baby New Year was featured alongside Father Time in the 1976 stop-motion animated film Rudolph’s Shiny New Year. In it, Happy (Baby New Year) goes missing, and if he isn’t located by midnight on New Year’s Eve, it will remain the old year forever. Because there’s a snowstorm, the titular reindeer is the only one capable of the task.

How do we celebrate Baby New Year today?

The image of Baby New Year is less prominent today than it was in the 20th century, according to Compora, but people still view the holiday as a time to start anew. “The spirit of rebirth or renewal is still present, but people apply it to themselves instead of looking for an artistic representation,” he says. “That’s why people begin the new year with resolutions designed to improve their lives.”

One of the last remaining traditions is fêting New Year’s babies born at the stroke of midnight. In the past, a baby born on New Year’s Day would be featured in local newspapers. However, even this custom is becoming less common, as many hospitals no longer share information on New Year’s babies with the media out of concerns about privacy and identity theft.

About the expert

|

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. For this piece on Baby New Year, Elizabeth Yuko, PhD, tapped her experience as a longtime journalist and researcher. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Daniel Compora, PhD, a professor in the department of English language and literature at the University of Toledo; email interview, Dec. 3, 2024

- Encyclopedia of New Year’s Holidays Worldwide by William D. Crump

- New Year: Its History, Customs, and Superstitions by Theodor Gaster

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities: “Vannus”

- Museum Crush: “Talking corn dollies and harvest spirits with the Museum of British Folklore”

- English Heritage: “Historical Autumn Traditions”

- California State University Northridge: “Victorian and Edwardian greeting cards”

- Saturday Evening Post: “New Year’s babies”

- CNN: “How ‘Baby New Year’ was born”