When is the next leap year? Here are some fascinating leap year facts, along with all the details about why leap day always falls on Feb. 29.

When Is the Next Leap Year? Leap Year Facts You Probably Didn’t Know

February is packed with interesting observances, but one that stands out is Leap Day—and the Leap Year that makes it possible! If you’re wondering “When is the next leap year?” or curious about why we have them in the first place, you’re in the right place. Let’s dive into the fascinating origins of leap years and share some fun facts along the way.

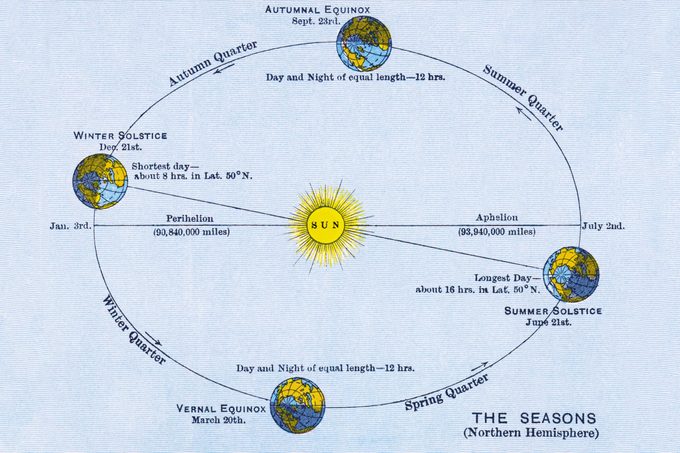

Here’s the deal: a solar year—the time it takes Earth to complete one orbit around the sun—lasts about 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes and 46 seconds. That leftover chunk of time adds up, and without leap years, our calendar would fall out of alignment with the seasons. So every four years, we add an extra day to February to keep things on track.

Leap years don’t just keep our calendars in sync; they’ve inspired quirky traditions, like women proposing to men, and create birthday challenges for the 1 in 1,461 people born on February 29.

If all this sounds a bit complicated, don’t worry—we’ve got you covered! Keep reading to find out everything you need to know about leap years, including whether 2025 makes the cut. Hint: it doesn’t!

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more holidays, humor, cleaning, travel, tech and fun facts all week long.

What is a leap year?

A leap year is a calendar year that has an extra day, compared with our common year. The point of leap years is to help adjust our Gregorian calendar (aka, the 365-day calendar you can find on your desk or phone) to the solar calendar, and make sure we celebrate solar events like the spring and autumn equinoxes with some regularity every year. But why is Feb. 29 called leap day? Well, because Feb. 29 is our extra day!

What would happen without a leap day?

If we didn’t have an additional day on Feb. 29 every four years or so, our calendar would slowly fall out of sync with the Earth’s orbit. Each year, we’d lose close to six hours, and over a century, this gap would grow to a staggering 24 days. Key seasonal markers, like the spring equinox or the winter solstice, would gradually drift away from their current dates. Imagine this: in just 100 years, September’s autumn equinox in the Northern Hemisphere would shift back into August. Fast forward a few centuries, and August could find itself welcoming the start of spring.

When is the next leap year after 2024?

While 2024 was a leap year, 2025 is not! The next leap year will be in 2028, followed by 2032 and 2036.

How often are leap years?

A leap year happens every four years, with an exception.

What is a leap second?

The leap second is the exception! A leap second is a second that is occasionally added to synchronize our clocks with the Earth’s rotation. Scientists once called for a leap second in 2015 on June 30 at 11:59:60 pm.

How do you remember if it’s a leap year?

Simple: If the last two digits of the year are divisible by four (for example, 2016, 2020, 2024, 2028 …) then it’s a leap year. Century years are the exception to this rule. They must be divisible by 400 to be leap years—so, 2000 and 2400 are leap years, but 2100 will not be one. As a bonus, U.S. leap years almost always coincide with election years.

Leap Year facts

1. What’s crazier than Feb. 29?

A woman proposing to a man, says history. Consider adding this historical fact to your list of trivia questions: After Pope Gregory XIII instituted the Gregorian calendar, the idea of adding Feb. 29 every four years seemed so ridiculous that a British play joked it was a day when women should trade their dresses for “breeches” and act like men. The play was meant as satire, but some early feminists must have been inspired; by the 1700s, women were using leap day to propose to the men in their lives. The tradition—now called Bachelor’s Day or Sadie Hawkins Day—peaked in the early 1900s and continues today in the U.K., where some retailers even offer discount packages to women popping the question.

2. The Salem witch trials are connected to leap day.

If we’re looking at history a bit closer to home, then we should focus on Massachusetts. The Salem witch trials weren’t a fun time in Colonial America, and there was a particularly negative connection with leap day. The first warrants for arrest in the Salem witch trials went out on Feb. 29, 1692.

3. It’s rare to be born on leap day … but what about dying on leap day?

According to the World Heritage Encyclopedia, in the 1800s, British-born James Milne Wilson, who later became the eighth premier of Tasmania, was born on a leap day and died on a leap day too! Wilson died on Feb. 29, 1880, on his “17th” birthday, or aged 68 in regular years.

4. What do Tony Robbins and Gioachino Rossini have in common?

They are both extremely successful in their respective fields—but more to the point, they were both born on Feb. 29. According to BBC, the odds of being born on Feb. 29 are 1 in 1,461, which makes it particularly rare for one leapling, as they are called, to meet another.

Rarer still is the possibility that three children in the same family would be born on three consecutive leap days, but that’s exactly what happened with the Henriksen family of Norway. Heidi Henriksen was born on Feb. 29, 1960, her brother Olav four years later, on Feb. 29, 1964, and baby Leif-Martin four years after that, on Feb, 29, 1968. According to many government agencies, the siblings would not legally be considered a year older until March 1 on non-leap years. In 2024, we could officially say “Happy Actual Birthday, leaplings!”

5. Only Swedes and Hobbits celebrate Feb. 30.

Feb. 30? This even rarer date occurred in Sweden and Finland in 1712, when they added an extra leap day to February to help catch up their outdated Julian calendar with the new Gregorian calendar. There is, however, one race of people who celebrate Feb. 30 every year: Hobbits. The wee folk of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings universe observe 12 extra long 30-day months every year—including Solmath (translated in the text to February).

6. There is an official leap day cocktail.

And it’s called … the Leap Day Cocktail! This colorful cousin of the martini was invented by pioneering bartender Harry Craddock at London’s Savoy Hotel in 1928. According to the 1930 Savoy Cocktail Book, “It is said to have been responsible for more proposals than any other cocktail ever mixed.” Whether or not you’re in the market for a freshly soused spouse, you can make your own leap day cocktail with Craddock’s original recipe:

1 dash lemon juice

2/3 gin

1/6 Grand Marnier

1/6 sweet vermouth

Shake, serve, garnish with a lemon peel and enjoy the flood of bittersweet flavors. It’s like a marriage in your mouth!

7. Celebrate leap day with travel deals and a rare French magazine.

How does one celebrate a holiday that’s not really a holiday? By shopping, obviously. Many businesses observe the rarity of leap day by offering massive deals. Take a minute to check in with any restaurants, hotels or cruise lines you’ve been curious about; chances are, they have a promotion running. And if your travels take you to France, pick up a copy of the rare La Bougie du Sapeur, a French parody newspaper only published once every four years, on leap day. Newsstand copies sell for 4.80 euros per issue, but generous investors can buy a lifetime subscription.

8. Is Feb. 29 good luck or bad luck?

Depends who you ask! According to an old Scottish aphorism, “leap year was ne’er a good sheep year.” The superstition that leap days are particularly lucky or unlucky has been debated through history and across cultures, and there’s still no clear answer. For one thing, it’s bad luck if you’re a prisoner on a one-year sentence that spans a leap day. Also, bad news if you work on a fixed annual salary—no extra pay for that extra day. On the other hand, leap day is great luck if you pay a fixed monthly rent (one free day of living!), or if you’re Hattie McDaniel, in which case Feb. 29, 1940, was the day you became the first African American to win an Oscar, for your role as Mammy in Gone With the Wind.

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Time and Date: “How Long Is a Tropical Year / Solar Year?”

- Time and Date: “Leap Day: February 29”

- Mental Floss: “The Ladies’ Privilege: Encouraging Women to Propose on Leap Day”

- Slate: “Get a Hustle On—It’s Leap Year”

- History.com: “5 Things You May Not Know About Leap Day”

- USA Today: “A few facts about leap day”

- BBC: “Leap year: 10 things about 29 February”

- Tolkien Gateway: “Shire Calendar”

- NPR: “For Leap Day Only, a Rare Newspaper Goes to Print”

- IMDb: “Hattie McDaniel”

- Time and Date: “What Is a Leap Second?”