Time to brush up on your knowledge of Winnie-the-Pooh facts! There's a lot more to the Hundred Acre Wood than you realized.

18 Winnie-the-Pooh Facts That Most People Don’t Know

Generations of children have grown up reading A.A. Milne’s stories of Winnie-the-Pooh and his friends in the Hundred Acre Wood. First published in 1924 and later brought to life in numerous films and television shows, Milne’s gentle, humorous tales about the honey-loving bear and his pals Christopher Robin, Piglet, Rabbit, Tigger, Eeyore, Kanga and Roo have captured imaginations around the world, inspiring deep collections of Winnie-the-Pooh facts and winning spots on lists of the best books for kids.

But everyone’s favorite silly old bear still holds a few surprises up his red sleeves. Read on for 18 bits of Winnie-the-Pooh trivia that you probably never knew.

Join the free Reader’s Digest Book Club for great reads, monthly discussions, author Q&As and a community of book lovers.

1. Christopher Robin was a real boy

Milne had one child: a son named Christopher Robin Milne. Though Christopher Robin went by the nickname “Billy Moon” at home, his father used his son’s given name in his Winnie-the-Pooh books. And yes, young Billy Moon had a stuffed bear he eventually named Winnie. (More on that later.) His father made up a story involving his favorite toy, and the rest is literary history.

2. Milne wasn’t initially a children’s author

Before penning the Winnie-the-Pooh books, Milne was a successful playwright, humorist and essayist, as well as an editor at Punch, a British humor and satire magazine. However, after becoming a father, Milne started writing for children. His first work for kids was a poem published in Vanity Fair in 1923 called “Vespers,” which contained the line “Christopher Robin is saying his prayers.”

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more books, humor, cleaning, travel, tech and fun facts all week long.

3. Winnie-the-Pooh’s original name was Edward

When the real-life Christopher Robin, aka Billy Moon, first got his stuffed bear, the family called it Edward—the formal version of Teddy. (As in teddy bear—get it?) But as Billy Moon got a little older, he became very fond of what was then the main attraction at the London Zoo: a black bear named Winnie. He made frequent trips to visit Winnie with his father and ultimately decided to rename his favorite toy.

4. The “Pooh” part of his name came from a swan

No list of Winnie-the-Pooh facts would be complete without an explanation for the “Pooh” part of the bear’s name. So where did it come from? As the story goes, that was what Billy Moon used to say to a swan he tried to feed in the mornings. When the swan wouldn’t cooperate, the boy would say, “Pooh!” in frustration. When it came time to rename his bear, he decided to go with a combination of his friend at the zoo and the swan.

5. The real Winnie has her own interesting backstory

In 1914, a 27-year-old Canadian veterinarian and soldier named Harry Colebourn—who was originally from England but living in Winnipeg, Canada—was traveling through Ontario en route to military training in Quebec. At a brief railroad stop, he purchased a 7-month-old black bear cub from a trader who had shot and killed its mother. Colebourn named the bear “Winnie” after his adopted hometown of Winnipeg.

He brought Winnie with him to England when he was deployed and gave her to the London Zoo for safekeeping while he was at war, but he promised to bring her back to Canada when the conflict was over. Soon, Winnie became one of the most popular animals at the zoo, thanks to her gentle demeanor. When Colebourn was discharged in 1918, he returned to the zoo to collect his bear, but he quickly saw that her home was now in London, where she was regularly visited by children, including the real-life Christopher Robin.

6. Sanders is not Winnie-the-Pooh’s last name

It’s best to approach the stories featuring Winnie-the-Pooh and his friends through the eyes of a child—in other words, not questioning what a tiger and kangaroos are doing living in the woods of England. But there’s one piece of Winnie-the-Pooh trivia that has baffled children and adults alike: the sign with the name “Sanders” over the door to Winnie-the-Pooh’s house. Does this make his full name Winnie-the-Pooh Sanders?

It’s highly unlikely. In the opening chapter of Milne’s first Winnie-the-Pooh book, published in 1926, here’s how he introduces readers to his main character: “Winnie-the-Pooh lived in a forest all by himself under the name of Sanders.” When Christopher Robin (the character in the book) asks the “growly voice[d]” narrator what “under the name” means, he’s told: “It means he had the name over the door in gold letters, and lived under it.” And that’s the extent of Milne’s explanation. There aren’t even any quotes from Winnie-the-Pooh himself that shed any light on the situation.

Over the years, many readers and experts have speculated that this means that the previous resident of Pooh’s hollow tree home had the last name of Sanders, and Pooh simply didn’t remove the sign when he moved in.

7. There may have been a real Sanders

There are two other theories about why that nameplate appeared over Pooh’s door, though both are unconfirmed. The first is that Ernest H. Shepard, who illustrated the books, had been injured in World War I and spent time in a British hospital with a Canadian soldier named Sanders. The man’s son, David Sanders, claimed in a 2014 interview that Shepard used his father’s name because the real Winnie bear had ties to Winnipeg. “Who did [Ernest Shepard] know from Winnipeg? … My father,” he told the CBC. “So that’s Mr. Sanders.” Unfortunately, hospital records that could potentially confirm the connection were destroyed during World War II.

The second explanation comes from Ann Thwaite’s 1990 biography, A.A. Milne: The Man Behind Winnie-the-Pooh. She writes, “The Sanders referred to was Frank Sanders, who had a printing works in the Snow Hill area of London,” and cites a 1989 interview with Frank’s nephew, Douglas Sanders, as the source of this information. While Thwaite says that Frank Sanders was friends with Shepard, she was unable to find any direct references from Milne that would confirm this reference.

8. Winnie-the-Pooh is 100 years old (sort of)

Winnie-the-Pooh’s age is a point of contention. Since the character first appeared in Milne’s 1924 book of poetry, When We Were Very Young, some consider that Pooh’s birthday—making him 100 years old. However, Christopher Robin received his stuffed Pooh toy on his first birthday, Aug. 21, 1921, which would make Pooh 103. Either way, Winnie-the-Pooh has been around for more than a century.

9. War led Milne to the Hundred Acre Wood

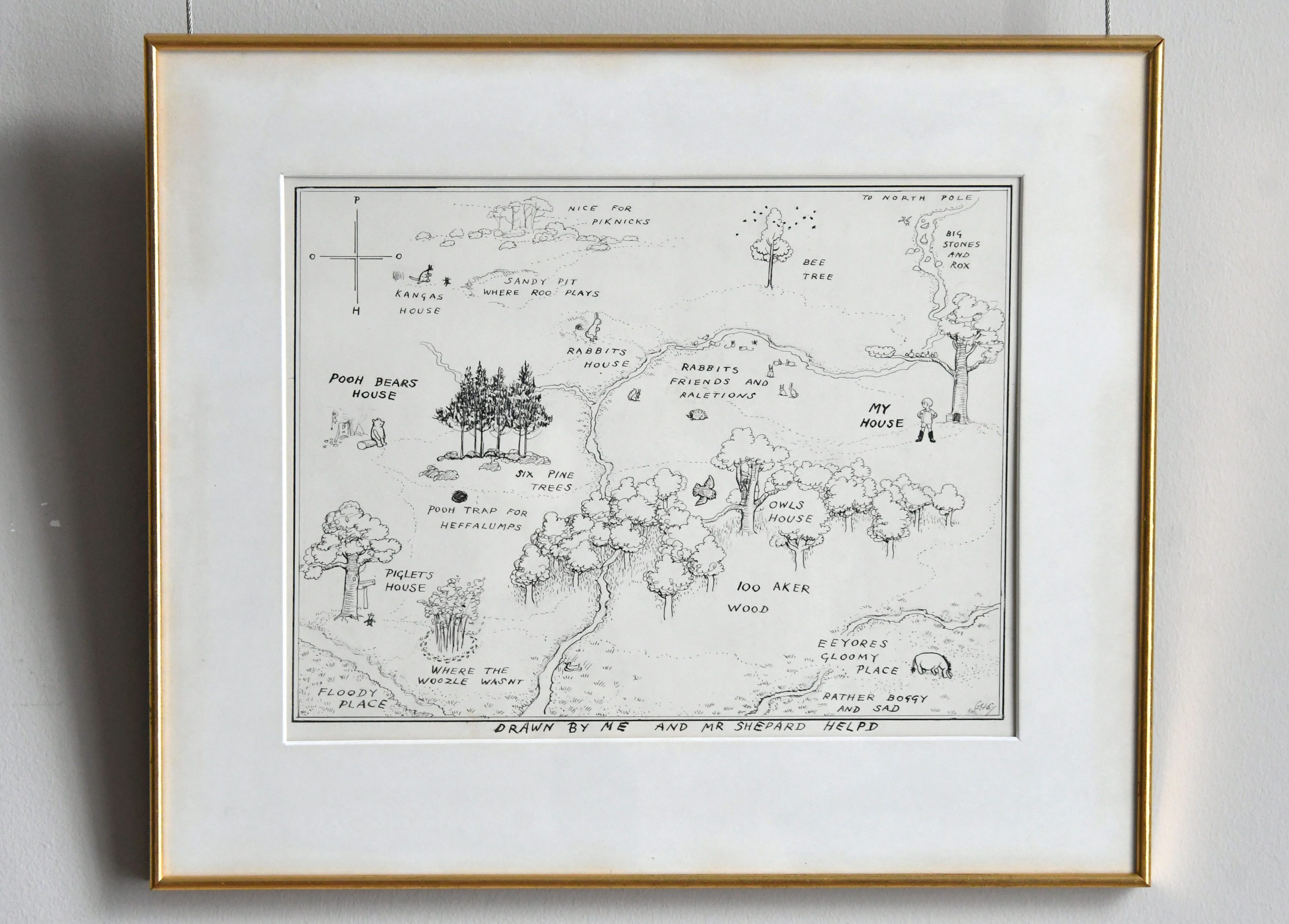

Milne served in the British Army during World War I, getting injured in 1916 at the First Battle of the Somme. He was left with what was then called “shellshock”—today, it’s known as post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD—and after the war, he moved his family from the busy streets of London to a rural part of the country in search of a quieter life, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Near their new home at Crotchford Farm, Milne and his son would frequently visit Ashdown Forest, usually with Billy’s toy bear in tow. The forest would ultimately inspire the Hundred Acre Wood, the setting for the adventures of Winnie and his woodland pals.

10. Winnie-the-Pooh first appeared in a poem

As noted above, the character of Winnie-the-Pooh first appeared in Milne’s 1924 book of poetry, When We Were Very Young. Specifically, the 38th poem in the book, “Teddy Bear,” features a “Mr. Edward Bear,” who would later become Winnie-the-Pooh. Not only that, but accompanying this children’s poem was a drawing by Shepard, who would go on to illustrate the books.

11. The plot of the first Winnie-the-Pooh story may ring a bell

Following the success of When We Were Very Young, Milne wrote a short story entitled “The Wrong Sort of Bees,” which was published on Christmas Eve 1925 in the London Evening News. Though it featured the same “Mr. Edward Bear” character from the poem, this time Milne changed the bear’s name to Winnie-the-Pooh. In the story, Pooh, who is perpetually hungry, tries to steal some honey from bees, using tactics such as rolling around in mud to look like a rain cloud and using a balloon to get up to the hive. This story became the premise for the 1966 Disney cartoon Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree.

12. You can visit the real-life inspirations behind the beloved characters

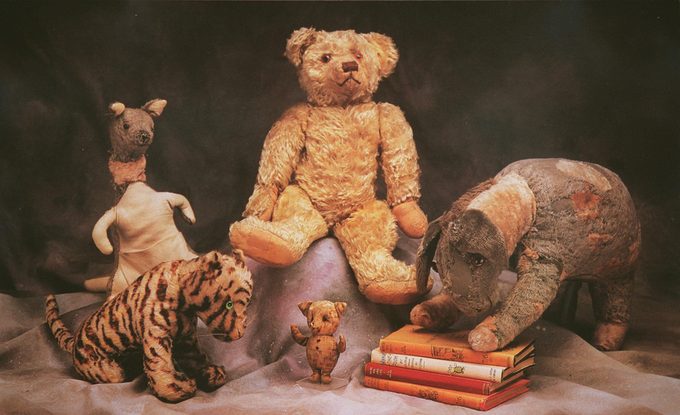

Believe it or not, the real-life toys that inspired the Winnie-the-Pooh characters and the classic books still exist. Better yet, you can visit them for free at the main branch of the New York Public Library! Since 1987, Pooh, along with Eeyore, Piglet, Kanga and Tigger, have resided at the library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building in midtown Manhattan—pretty far removed from the Hundred Acre Wood. The toys all belonged to the real-life Christopher Robin. He received each of the stuffed animals as gifts between 1920 and 1928. (If you’re wondering about the rest of the gang, the stuffed Roo was lost and there were no toys to inspire Rabbit and Owl; Milne just made up the characters.)

13. The same illustrator is responsible for all the Winnie-the-Pooh drawings

Shepard, who did the illustrations for Milne’s 1924 book of poetry, stuck with the author throughout the rest of his children’s books. According to Smithsonian Magazine, “the prose and drawings of the Hundred Acre Wood animals, and their young human friend, were a perfect match, capturing the wide-eyed innocence and thrills of childhood, but with an underlying bit of melancholy and sadness.” In addition to their working relationship, Shepard and Milne shared the experience of being combat veterans.

14. The first book of Winnie-the-Pooh stories was an instant hit

After a poem and a short story, Milne was ready to expand his magical world in the Hundred Acre Wood into a book. Published in October 1926, the collection of stories, simply titled Winnie-the-Pooh, was immediately popular both in England and abroad. Approximately 32,000 copies of the original British version were sold in the United Kingdom, while sales reached 150,000 copies in the United States—all by the end of 1926. Think of it like the early-20th-century version of the Harry Potter series.

15. The real Christopher Robin came to resent his fictional counterpart

So what did Christopher Robin really think about Winnie-the-Pooh? Though Milne’s son initially enjoyed the fame, he later came to resent it. When Christopher Robin went off to boarding school in 1930, he endured teasing by his classmates. One incident involved his peers repeatedly playing a gramophone record he lent his voice to, then getting upset that he smashed it. Christopher Robin became especially resentful during his post-university job search in London. “In pessimistic moments, when I was trudging London in search of an employer wanting to make use of such talents as I could offer, it seemed to me, almost, that my father had got to where he was by climbing upon my infant shoulders, that he had filched from me my good name and had left me with nothing but the empty fame of being his son,” he wrote in his 1974 memoir, The Enchanted Places.

16. A Winnie-the-Pooh book is the only New York Times bestseller in Latin

Not only were the initial sales of the book phenomenal for the time—their popularity has continued since. In fact, it’s never been out of print, and sales exceed 20 million copies in 50 languages, including Latin. First published in 1958, a Latin translation of the book, Winnie ille Pu, is the only book in Latin that has ever appeared on the list of New York Times bestsellers.

17. The success of Winnie-the-Pooh may have hurt Milne’s career

Though Milne wrote only four books containing stories about Winnie-the-Pooh and his friends in the Hundred Acre Wood, the characters would follow him for the rest of his life. In fact, when Milne attempted to return to writing for an adult audience, he found that readers wouldn’t accept him as anything but an author of children’s books. “His skill had not deserted him, but his public had; and eventually the editor, E.V. Knox, wrote to tell him so,” Christopher Robin wrote in his memoir. “We each had our sorrows.”

18. The voice(s) of Winnie-the-Pooh may sound familiar

Veteran voice actor Jim Cummings has been the voice behind Winnie-the-Pooh in more recent movies like Piglet’s Big Movie (2003), Pooh’s Heffalump Movie (2005) and Christopher Robin (2018). It’s no surprise if his voice sounds familiar, as he’s provided the vocals for characters in other animated films including Disney’s Aladdin (1992) and The Princess and the Frog (2009).

Before Cummings, actor Sterling Holloway first brought Pooh’s voice to life in the 1966 Disney cartoon Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree, and perhaps most notably in The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (1977). He also voiced the Cheshire Cat in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland (1951), Kaa the snake in The Jungle Book (1967) and Roquefort the mouse in The Aristocats (1970).

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’ve been sharing our favorite books for over 100 years. We’ve worked with bestselling authors including Susan Orlean, Janet Evanovich and Alex Haley, whose Pulitzer Prize–winning Roots grew out of a project funded by and originally published in the magazine. Through Fiction Favorites (formerly Select Editions and Condensed Books), Reader’s Digest has been publishing anthologies of abridged novels for decades. We’ve worked with some of the biggest names in fiction, including James Patterson, Ruth Ware, Kristin Hannah and more. The Reader’s Digest Book Club, helmed by Books Editor Tracey Neithercott, introduces readers to even more of today’s best fiction by upcoming, bestselling and award-winning authors. For this piece on Winnie-the-Pooh facts, Elizabeth Yuko tapped her experience as a longtime journalist and avid researcher to ensure that all information is accurate and offers the best possible advice to readers. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Smithsonian Magazine: “How Winnie-the-Pooh Became a Household Name”

- History.com: “The True Story of the Real-Life Winnie-the-Pooh”

- Biography: “A.A. Milne”

- New York Public Library: “Happy Birthday, Winnie-the-Pooh!”

- CBC News: “Sanders name has deep Winnipeg roots, from gavels to Pooh”

- Washington Post: “The Natural World of Winnie-the-Pooh Is a Honey Pot of Nostalgia”